Repton Village Website

Repton - historic capital of Mercia

Reminiscences of Repton

These articles appeared in the Parish Magazine in 1980 - it is interesting to note how much has changed since then.

Bygone Repton

Among

the records of one of the older residents of Repton is this description of

an old custom:

On the

nearest Friday to 11th October a Statutes Fair was held at the Cross,

where farm-servants waited to be hired to live in. As soon as they

obtained a ‘place’ and had accepted one shilling, they pinned on a

bunch of coloured ribbons and began to enjoy the fun of the fair.

Stalls

for gingerbread and sweetmeats were set out around the Cross together with

various shows. Each one of these paid a levy to the Lord of the Manor.

There is a legend that, like Michael Henchard in Thomas Hardy’s Mayor of Casterbridge, a man did actually sell his wife in Repton.

A Reminiscence of Childhood

One of my most treasured memories of Repton village is of Mrs. Pentlow and her shop.

This was the front room of the house nearly opposite the old village

school. After mounting two steps

To the right of the front door one entered the shop again, grey paint work and carmine walls each well stacked with, to a child’s eye, very exciting things! Wool in skeins, embroidery silks, cotton reels in small boxes of a dozen or more, stockings, tray-cloths to be embroidered, in fact, all things needed by the average housewife. On the customer’s side of the counter was placed a rather dainty long-legged bentwood chair ;this enabled her to linger over the great decision to purchase the goods of her choice and also to pass the time of day with dear Mrs. Pentlow.

Behind the counter was a black fireplace always beautifully polished. I could never determine whether I preferred the summer months when the blind was hung over the window on the outside (we had to undo small rings fastening it to peep in) or the winter when there was a lovely fire in the black grate. Mrs. Pentlow always sat between the fire and the window facing the door, looking very calm, fragile and Edwardian, her soft hair always very neatly arranged and covered by a fine hair net. She dressed in black, but what fascinated me was the boned high lace collar (hand-made of course) enhanced by a black velvet band fastened by a brooch. When I was about twelve years old I made and presented her with a small turquoise-coloured bead-type brooch which to my delight she often wore. Her spectacles were small, round and gold rimmed.

The window was choc-a-bloc with examples of her wares; small dolls,

teddy bears, wools and baby clothes, but the most intriguing part of the

shop to me was a large glass-topped case on the counter. This was filled

with rolls and rolls of silk ribbon ;the smell when this case was opened

still haunts me - a delicious aroma of good silk.

In those days I had two long fair plaits and unknown to my mother I

often lost on purpose my hair ribbons purely to have the delight of

opening the case and choosing new ones. Words cannot describe the sheer tranquillity of Mrs. Pentlow

and her shop. This saddens me because in this age such shops and

personalities

Mrs Pentlow’s husband in his younger days was valet to the Earl of Carnarvon. He had many fascinating tales to tell me of his travels to Egypt and other places. Again a lovely memory is going to his allotment situated down Laundry Lane (Tanners Lane). To reach his garden one climbed wooden steps placed in the bank. The garden in Summer was ablaze with flowers of every conceivable colour, mainly cottage types. I was in the seventh heaven when I was allowed to pick a huge bunch to take home to my mother. - Happy memories.

The

Little Shops of Repton

In a

short article only a few can be referred to in detail. All were valuable

in their day and we hope no feelings will be hurt by inevitable omissions.

The only businesses, apart from the farmers’, that remain at all as they

were are the blacksmith’s, Mr. Wain’s; Sanders, the builders; Mr.

Coates’, the butchers; and the post office.

There

were a considerable number of food-shops: three bakeries existed, Mr.

Melen’s at the Stone House; one at the back of the Shakespeare Inn; and

Taylor’s ‘Bottom Shop’ in the Square. This is now Mr. Burdett’s

newspaper, cigarettes and confectionery business. But we didn’t lack for

confectionery, most of the shops had jars of sweets - but the epitome of

both bakers and confectioners was Miss Daisy Holmes, who made the most

delicious table delicacies in an incredibly small kitchen-cum-shop in

the front-room of her cottage between New House and the Red Lion. There

was only room for one customer at a time besides the oven, the work-tops,

the counter and the cook herself. The great thing for birthdays was a

‘Daisy cake’, made to the recipient’s own taste and beautifully

decorated with roses or forget-me-nots, even lilies-of-the-valley or

daffodils. Would that they were still available!

At

different times we boasted three fish and chip shops: one beyond the

Shakespeare in Main Street, one a part of what is now the British Legion

car park and Mr. Pike’s on the Burton Road. This shop was rebuilt by Mr.

and Miss Perry as a greengrocery, and finally taken over by the present

owner, Mr. Forbes.

There

were at least three butchers: Coxon’s that became Beeston’s; Leslie

Brown’s, now Coates’s; and Matthews’. This last was kept by two

brothers with the picturesque names of Farmer and Porter. Farmer fattened

his own beasts, and never quite regained his spirits after the war put an

end to this and he had to sell ‘what he was sent’. Porter is still

around. He took the orders and delivered the meat and the milk, and was

known to oblige at least one customer and old friend by sharpening her

knives, once a week, while she plied him with a welcome cup of tea.

Front-room

drapers abounded. Mrs. Pentlow our readers already know, but Miss Pearson

and Mrs. Marshall side by side almost at the Square, had each her own

clientele, and each made a living.

There

were several cobblers : Sam Collier, adjacent to the blacksmith, Mr. Cook

succeeded by Wilfred Bull in Keiston Lodge Drive, and Mr. Elson in the

drive to Garden Cottage. He it was who electrified a town-dwelling

newcomer in the early thirties by telling her that he would have no

leather to repair her shoes ‘until the boys came back’. She met the

same story when she went to buy biscuits at the grocer’s. After that,

she retreated for a fortnight, conscious of her own insignificance.

I believe

the Billiard Hall in the High Street was built in 1921 with a shop-front.

The first chemist to use this was Mr. Mansell who came in 1925 and

was succeeded in 1928 by Mr. G. W, Kenny who, in his turn, was followed by

Mr. J. E. J. Parkinson in 1947. Our present chemist, Mr. J. Spencer has

been with us since 1967, and we much hope to have his kindly, friendly

service

for many years yet.

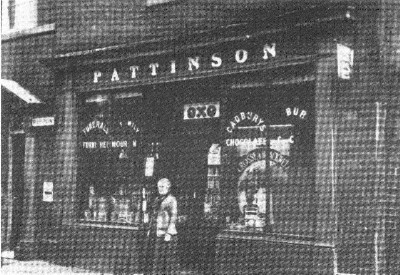

It is

not very clear when Mr. Pattinson’s general shop at the top of High

Street became the post office, but some of his grocery business remained

with it. In the twenties Mrs. Pattinson, mother of Mrs. Stella Adams, who

was her assistant, did a thriving trade there. Mrs. Pattinson lived and

worked to a very great age, and can be remembered in her tight-bodiced

black dress taking the money but feeling it to check it and give change,

for her sight was bad. When she retired so did Mrs. Adams.

Subsequent

Postmasters were Mr. Morris and Mr. Sinclair, before Mr. Robinson came in

1958. We all value him for his constant helpfulness and his general

knowledge of and concern for the whole village.

In the

last century the grocer’s shop in the High Street was kept by a Mr.

Skevington. One of their travellers, even then a very old man, told Mrs.

Thelma Blunt years ago, that the shop had also been the Post Office, and

that he himself had taken there the first telegram that ever came to

Repton.

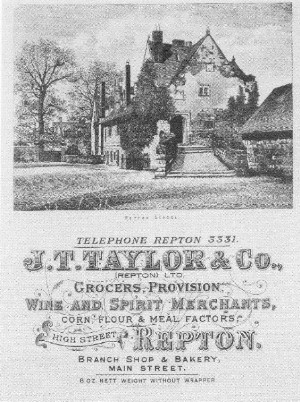

According to an old price list, dated 1900, the shop was by then owned by a young man, Mr.J. T. Taylor. He ran it alone until he was joined by Mr. Ernest Blunt who came as an ‘improver’. He became consecutively partner and then owner, and ran the shop until his death. His daughter, Thelma, now Mrs. Goodall, and his son Lionel, worked with him for many years. It was a most friendly place, always smelling deliciously of freshly ground coffee, where we all gathered and chatted with the shopkeepers and each other as we still do in the shops that are left. Eventually the business was sold to a Mr. Everington who tried self-service, but this did not succeed, and the grocery gave way to ‘Reptonia’ and the Estate Agents.

REPTON

IN WAR-TIME

Growing

up

Repton

must have been one of the safest places in England for a child to grow up

in during the war years. Nothing dangerous ever happened. Nonetheless, the

first stage of the war was frightening despite the near-normality of

everyday

life. Our generation had been reared on firsthand war

stories; we all knew where our dads

had been in the Great War. Gassed and disabled veterans were a part

of our community. So, when we were issued with our gasmasks and told to

carry them at all times, fear of survival touched our lives. There were

further ominous signs; air raid drills, black-out and a barricade along

the Willington Road. I don’t know whether the adults visualised

themselves manning such a defence but in my imagination it brought

goose-stepping Germans right inside our homes.

Quite

soon we got used to war time —

ration books, evacuees, wireless

bulletins, village boys in khaki. We stopped carrying gasmasks, didn’t

bother with the air raid shelter and climbed all over the invasion

barricade. There were a few memorable incidents; the plane which came down

at the back of the bank, the bomb crater out Milton way, to which we

trudged one Sunday, and the coming of the G.I’s. Apart from these, it

was all so normal.

Besides,

war brought benefits. All the adults were busy and purposeful. They were

earning money and we were better off. Community projects prospered as

never before Guides, G.F.S. and, most important, Toddy’s pictures.

Children spent a lot of time collecting things such as waste paper, rags,

rosehips and even nettles. I am not sure how useful these endeavours were.

The main benefit for us was that we saw ourselves as contributors.

Wartime austerity actually expanded our sense of usefulness. In this, we

were very lucky.

Margaret

Liebeschutz (née Taylor)

A

Reception Area

One of

my keenest memories is of the evacuees. Boys from King Edward’s School,

Birmingham, who came to join Repton School, were billeted all along the

village. They stayed for a year, during which there was no war activity

here, and they all went back home. Immediately following them came another

school from Birmingham of little children, most of whom had never been in the country

before. Many funny stories are told of what they said and did, but one of

the most touching is of the little girl sitting very quietly behind a desk

while Mrs. Neil Thompson and I arranged their billets. As we had almost

finished a little voice piped up, ‘Please take me missis’ —-which I did,

along with another small girl. I still hear every Christmas from Hazel, as

indeed I do from one of the great six-footers from King Edward’s who was

first billeted on me.

When the

second lot of evacuees had left and my husband went into the army he

handed me a starting pistol to alert my next door neighbour, Billy James,

an elderly man who was our air-raid warden. I used it once only when I

feared the house was being burgled. He came immediately, and found that

the cause of my alarm was the scraping of a falling clothes prop against a

window! Another memory concerns the collection for war material of

aluminium household utensils. These were whipped from under our noses by

determined collectors, who took off even the colander into which I was

cutting the beans for dinner.

Activities

ranged from gathering great armfuls of foxglove spears for the manufacture

of digitalis to one of my biggest jobs canning fruit and vegetables with

the WI at Newton Solney. We were trained by a representative from the

County Rural District Economy Centre; we acquired canning machines and

cans, and anyone who brought produce, and the sugar for fruit, could have

their canning done for them free of charge.

Winifred Riley

Repton

in Wartime — The

Farmer Speaks

A

well-known farmer in the neighbourhood feels that in the long run, the

war benefited farming. It taught the English farmers a big lesson for they

learned the hard way, to improve their husbandry. ‘The land likes to

work’, he says, and it thrives under pressure and care. By the end of

the war the countryside was in excellent shape: hedges trim, ditches

clear, the soil in good heart. All farmers and farm workers were required

to stay on the land. Immediately war broke out they received Government

instructions to plough a proportion —

about a

third of all their land, and to grow upon it certain specified crops

The

prisoners of war, in their brown uniform with the large white disc

on the back, were a changing population, for they were periodically

exchanged for British prisoners. The Italians who came first were mainly

town dwellers and found life very hard, but some were excellent farmers.

One

of Mr. Prothero’s two Italians was married by proxy to his Italian fiancée,

who later joined him here. He became Mr. Prothero’s right-hand man and

stayed with him until his retirement. Eventually he left farming and is

now a ticket-collector at Derby Station. Another has remained in the

district and is now a freelance mechanic working largely on agricultural

machinery.

One

of the farmer’s chief difficulties was the amount of paperwork entailed:

he must make accurate returns for all his production in order to get

coupons for his supplies. The allocation of these he managed for himself:

so many for cattle-feed, so many for fertilisers, others for fuel,

tractors

and so on.

Bendall’s

farm, for example, was mainly concerned with dairying. Understandably

the biggest customer was Rolls-Royce, which, working round the clock in

three shifts, required 600 gallons a day to be delivered in bottles.

Eventually when bottles became scarce the milk was delivered in churns and

the men collected their rations in their own mugs. Any surplus milk should

have gone to the cheese-making factory, but this was too far away and one

farmer certainly fed it to his pigs. This made lovely pork, but he was

only allowed to kill for his own use one or two pigs a year, and this by

special permission. The farmer’s wife had no easy task. She had

always, by tradition, fed the farm hands, with extras at harvest,

haymaking and threshing. She must have ration cards for them all to obtain

her essential supplies of tea, fats, sugar and milk, and she satisfied big

appetites as best she could.

But

on the whole, the conclusion seems to be that it all worked well. There

was ‘tremendous’ co-operation. Allocations were very fairly made and

with good management and hard work beasts and personnel were adequately

fed,

furthermore

some of the methods developed during the war, for example, the increasing

use of machinery and particularly the method known as ‘alternate

husbandry’, proved so good that they are still in use today.

Copyright and Disclaimer

All information on this website is copyright and permission must be sought before any form of electronic or mechanical copying. The information contained on this website has been included in good faith but the authors are not responsible for any liabilities resulting from its use.